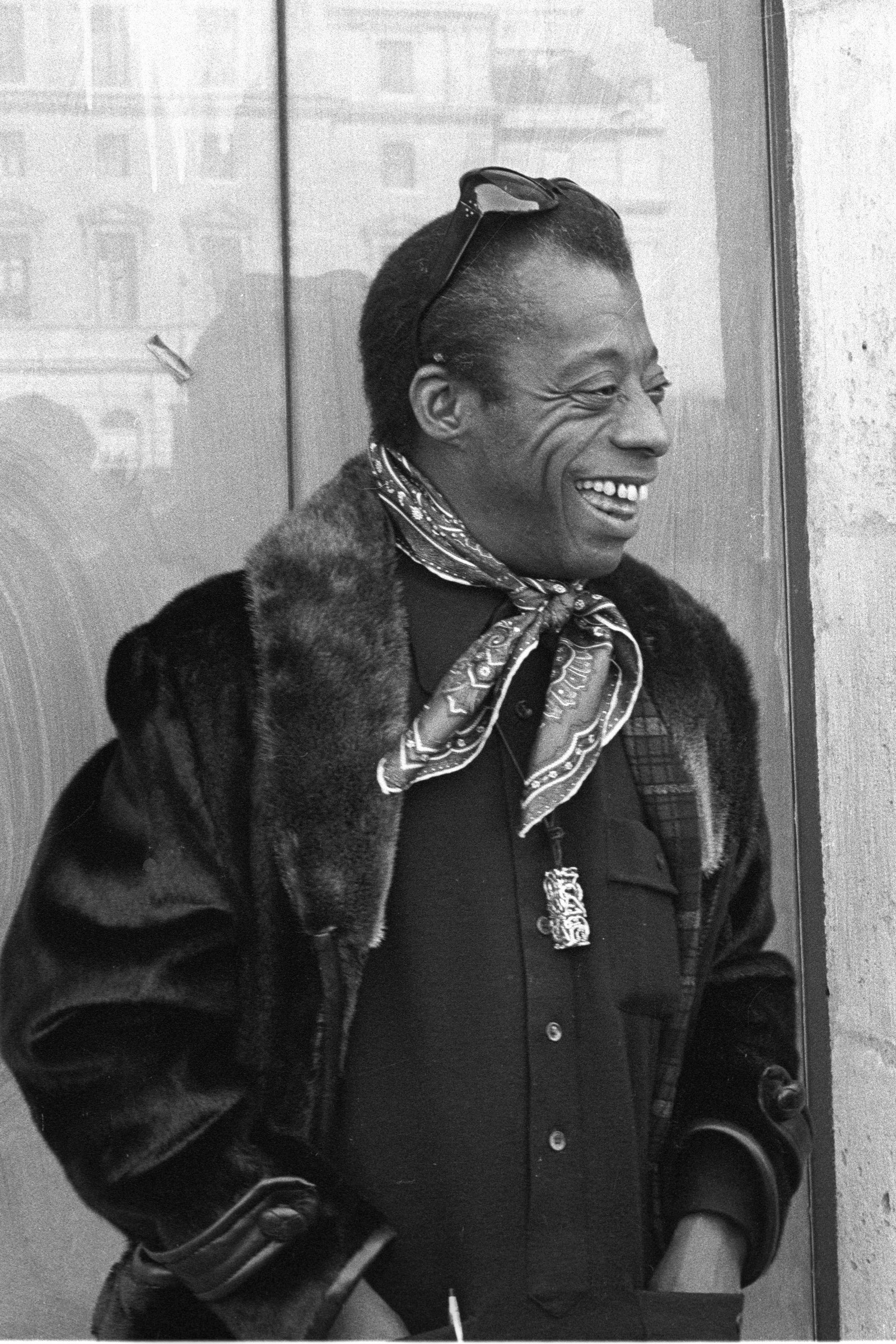

Born a generation later, James Baldwin, like Hurston, did not wear his wounds; instead, he wore sunglasses. Scarves. Coats with sharp collars and clean lines. His wardrobe wasn’t extravagant, but it was exacting, each garment chosen like a well-placed word.

He dressed the way he wrote: with rhythm and always in response to what the world refused to see. In New York, his taste for three-piece suits echoed the careful tailoring of the Harlem Renaissance: square shoulders, fine fabrics. Then, in Paris, he shed the weight. In the late 1940s, the rise of racial violence and McCarthyism, which targeted LGBTQ+ individuals during the so-called Lavender Scare, made life in the United States precarious for Baldwin as a Black queer man. So he fled to Paris, a longtime haven for artists like Josephine Baker and Richard Wright. There, he honed his insights on race, power, and belonging and finished his first published novel—1953’s Go Tell It On the Mountain—and drafted 1956’s Giovanni’s Room as well as several essays in his 1955 collection Notes of a Native Son. He also adopted minimalist trench coats and slim-cut suits that aligned him with the intellectual bohemianism of the Left Bank and the clean, architectural lines soon popularized by Pierre Cardin. Later on, in Istanbul, where he would spend much of the 1960s, Baldwin embraced more fluid silhouettes, his look standing apart from both the uniformed militancy of the Black Panther Party and the psychedelic flamboyance of the counterculture movement at home.

He never surrendered to full European assimilation, however. The edge of Harlem lingered: a ring, a fitted turtleneck, the way he stood. Baldwin wasn’t trying to disappear, but neither did he want to be fully read. His style was a cipher: queer, cosmopolitan, controlled.

Figures like Du Bois, Hurston, and Baldwin stitched freedom into fabric—not out of vanity but vision. To revisit their style is not nostalgia; it’s instruction, a reminder that to be Black and dressed is to be in theory, in process, alive.

So who carries their energy now? Prince did, for a time. In lace blouses and four-inch heels, he dressed like no one else dared. But his genius was not in extravagance; it was in the way he made space for others to dress their truths, to treat fabric as language and silhouette as statement. Similarly, Iké Udé’s self-portraits are less about fashion than authorship, building a counter-history of Black elegance. Ekow Eshun curates style like a scholar curates theory. Solange Knowles lives in her visuals: chrome, cowries, cloth—none of it arbitrary. And Grace Wales Bonner doesn’t just design but excavates. Her garments are essays in cotton and wool.