A young, blonde woman walks into a coffee shop and asks for a staff discount even though she doesn’t work there. Unsurprisingly, the staff say no. “It’s never as scary as you think,” says content creator Sophie Jones in a video posted to TikTok. “[Seeking out rejection] really helps me not take things so seriously,” she explains. In another video on the app, one woman puts her phone down in the street and starts dancing. Another asks a stranger for a hug.

The women, from all walks of life, claim to be practicing “rejection therapy”, a self-help concept that essentially means becoming desensitized to knock-backs through habitual exposure to rejection. Rejection therapy has become so trendy (with over 42 million posts on TikTok) that people on social media are regularly seeking out cringe interactions — from applying for a job they aren’t qualified for to asking a stranger to race them — in a bid to combat social anxiety and become more confident. I don’t know about you but for those of us who grew up Black and encountered racism on our doorstep, our mere existence often feels like a relentless form of rejection therapy. What happens when rejection isn’t something you seek out voluntarily but instead is thrust upon you regularly from childhood?

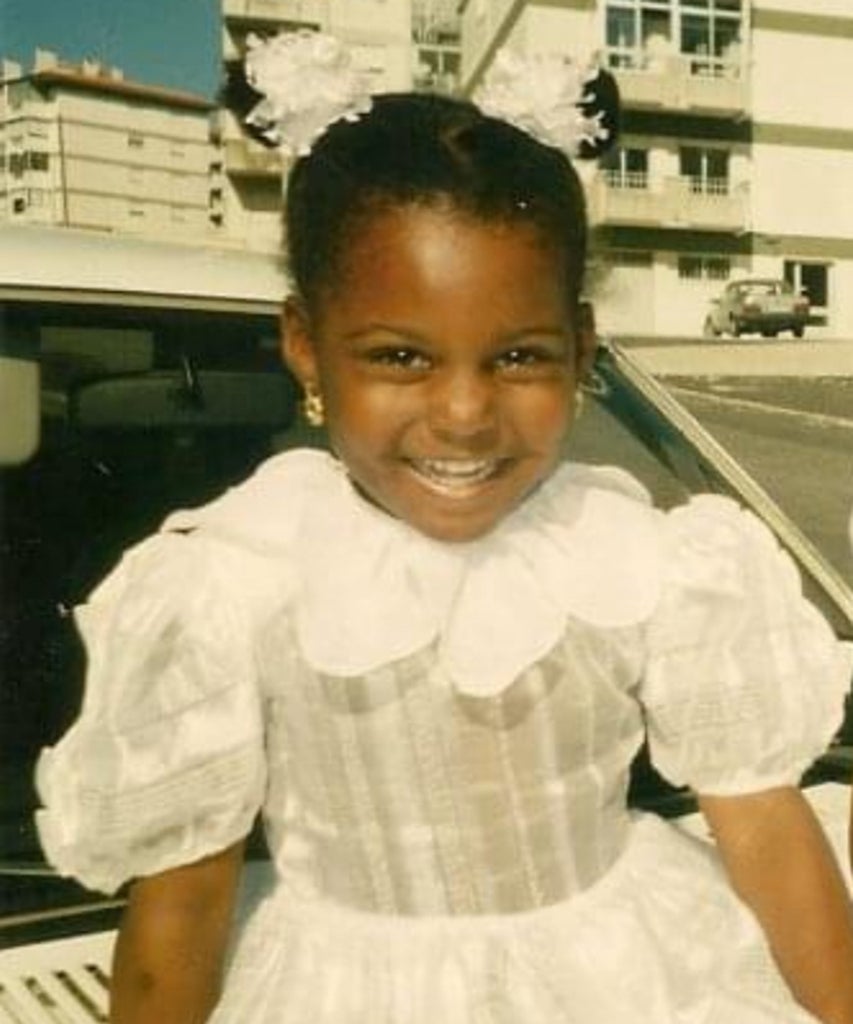

I discovered racism relatively early in life as I navigated being the only Black girl in the room for most of my childhood and well into higher education in the UK. Rejection has been an unwanted companion for as long as I can remember. I felt unwelcome in the street where I spent some of my teenage years, especially when neighbors called the police after my dad stayed out past sunset doing the gardening (I guess they feared he was planting tomatoes by day and burying bodies by night). Strangers heckled me and called me a witch as I walked home from school rocking my afro. I had racist teachers who couldn’t care less for my existence or my education. And I know I’m not the only Black person who has been followed around a store by staff who assumed I was there to steal rather than shop. Like many ethnic minorities in the UK, I have been personally victimized by xenophobes telling me to “go back to your country!” This stings particularly hard in light of the ongoing racial tensions in the UK, highlighted by this summer’s riots.

Sure, for every rejection there has been an abundance of love, acceptance and attention in my life, and upon reflection I know that I lived a beautiful and happy childhood. However, while racist incidents don’t taint my happy experiences, racism, and discrimination were entrenched in the communities I frequented and probably did affect my psyche. So I question whether I am a good candidate for rejection therapy or whether I have already benefited from years of involuntary exposure to rejection.

“Rejection therapy is more of a self-help challenge that you would do on your own. It’s not something you would practice with a psychotherapist but it’s very similar to exposure therapy, something I walk through with a lot of patients to treat phobias, social anxiety, and even OCD and PTSD. It’s one of the most commonly recommended forms of therapy for those [conditions],” explains associate marriage and family therapist Vendela Williams-Medearis.

Involuntary exposure to rejection is not necessarily [a form of] therapy. If out of control, it can lead to feelings of exhaustion, frustration and heightened anxiety over time, especially if you don’t have adequate coping mechanisms or support.

Vendela Williams-Medearis, Associate Marriage & Family Therapist

On the face of it, rejection therapy is a quirky way to confront your fears, push yourself out of your comfort zone, and become more confident. However, many Black people who experience excessive exposure to rejection in the form of overt and covert racism are forced to rely on survival mechanisms that aren’t always healthy. For some Black women, this means internalizing expectations of rejection and avoiding asking for help out of fear of being dismissed or misunderstood. It can also mean bracing yourself for a “no” rather than hoping for a “yes” as a form of self-preservation.

Williams-Medearis is no stranger to this sentiment as she too grew up as a Black woman in a similar monogenous environment. “Involuntary exposure to rejection is not necessarily [a form of] therapy. If out of control, it can lead to feelings of exhaustion, frustration, and heightened anxiety over time, especially if you don’t have adequate coping mechanisms or support. The other thing about anxiety is that it can keep you from setting goals that are achievable and limiting yourself to goals that feel safe,” she tells Unbothered.

Whether it’s microaggressions concerning Black hair and “professionalism”, reactions to our foreign surnames, or our unwavering desire to excel (which can be intimidating to bosses who don’t want you outshining them), when you’re a Black woman, rejection in the workplace can feel pretty relentless. If you’re not getting rejected for the job itself, it’s the promotion, or that big project you’ve been preparing and championing your whole team for… A 2022 survey from the New York-based think-tank Coqual found that over 50% of Black women in the UK were planning to quit their job due to racial inequalities.

“I’ve experienced rejection in the workplace,” says Naomi, 27, who works in law. “I remember having an old supervisor who always praised me and we never had any issues. However, when I got promoted to his role and built a rapport with (our now) joint boss, he then decided that I was cold and hard to work with and dismissed my superiority. He did that to other women that looked like me.”

It’s also crucial to examine the effects of rejection when dating and in relationships because dating experiences, good or bad, can deeply influence self-esteem and personal identity. The dynamics of dating can vary greatly depending on race, with Black women often facing unique challenges rooted in systemic racism and societal biases that others may not encounter.

“Choosing to date in itself [especially as a Black woman] is rejection therapy,” says Naomi. “Growing up I’d never felt like an asset in the male gaze when dating, other than by someone who is known to fetishize Black women,” she adds.

“In school, the one time people would say, ‘Oh, I think he likes you,’ was for the single other Black guy in my grade,” confides 29-year-old HR officer Olivia. “Nothing happened there but it was a known thing that [as a Black girl] you couldn’t be an option for anyone else (more for me than him, as him dating a non-Black woman was not seen as surprising). It almost made me feel like, Why even try because you will be rejected by default.”

The pervasiveness of Western beauty standards might have something to do with it. The lack of positive representation of Black beauty in the media reinforces the desirability politics at play, where beauty is often defined through a Eurocentric lens. This marginalizes and devalues the unique features of Black women, not only affecting a Black girl’s self-esteem but also shaping how society perceives us. It could be argued that this exclusion is another form of rejection. I never questioned my beauty, though. I adored my heritage and was always taught that my intelligence was currency and that was categorically indisputable — so thankfully this did not keep me up at night.

It’s no surprise that all my experiences of rejection compounded to leave me feeling surprised and at times resistant to genuine moments of acceptance.

Williams-Medearis believes that this element of involuntary exposure therapy was beneficial for me, likely due to my upbringing. “If you’re a Black woman who grew up in a household where you’re told that you’re beautiful, smart, and worthy, and then you go outside of your house and are told you’re not those things, are you going to immediately believe those people or will you have those uplifting voices at home be louder? Often, it’s the latter. However, if you’re getting the same discouraging messages at home as you are outside, you’re likely to believe them as they’re the only messages you’ve received.”

Mainstream conversations about rejection therapy ignore these racial nuances and, ultimately, it is a flawed concept. It assumes that all rejection is equal, failing to recognize the deeper emotional and psychological impact that racial rejection can have. It also fails to acknowledge how people with ADHD, like me, can experience anxiety and be more sensitive to rejection than the average person as a result of rejection sensitive dysphoria. Instead of having an empowering effect, rejection therapy can exacerbate feelings of alienation.

By the time I got to university (with people from more diverse backgrounds), I started getting some attention. However, it’s no surprise that all my experiences of rejection compounded to leave me feeling surprised and at times resistant to genuine moments of acceptance. It was not that I couldn’t fathom the idea of being embraced and liked outside of my safe spaces, but more that I wasn’t necessarily equipped to receive it.

Williams-Medearis reminds me that those feelings of uncertainty and resistance to receiving acceptance can have lasting implications for your self-esteem, which can affect your decision-making when it comes to dating and partner selection. “Having those expectations — I’m not good enough for a relationship, or for someone who likes me and is good to me and actually wants to pursue me — can lead to you settling into unhealthy relationships,” she adds.

There are ways to get rejection therapy to work if you follow an organized exposure approach. “You would want to create a hierarchy, [starting] with the least distressing thing to the most distressing thing,” advises Williams-Medearis. “With [seeking out] rejection, you would start with something low stakes, maybe [sending] a message,” she adds, also reminding me that the exposure itself is not enough to build confidence. “The other part of it is the response. So after it, you’re supposed to not use your safety behaviors, which would be any defense mechanisms, e.g. using distractions or seeking external validations.”

I have always believed that my independence and carefree approach to life are examples of using my strength as a badge of honor, which also means that I rarely allow people to see me fold. But that has cost me in the past. When Black women adhere to the idea of strength above all else, we ignore the psychological toll of constant rejection, even when we’re struggling. While it’s true that many of us have developed resilience out of necessity, it is a harmful narrative that portrays Black women as intrinsically stronger, more resilient, and able to endure more than others due to our involuntary exposure to rejection from society.

As I reflect on these common experiences many Black folks like myself share, I’m reminded of the importance of rejecting the idea that Black women should have to be exposed to rejection to overcome society’s bias and misogynoir. “Rejection therapy in this context can probably be helpful for some people, but most importantly you should build up the language of acceptance,” says Williams-Medearis. “In the real world you’re going to get ‘no’ maybe 50 times before you hear a ‘yes’ (if ever), but what’s important is how you talk to yourself afterward. Identify the feeling, accept it, and move on.”

This article was originally published on Unbothered UK

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?